In a significant loss to the literary world, Robert Gottlieb, a renowned editor who shaped the library of novels, nonfiction books, and magazine articles by a plethora of acclaimed writers from the mid to late 20th century, has died at the age of 92. His wife, Maria Tucci, confirmed his passing on Wednesday in Manhattan.

A trailblazing figure in the publishing industry, Mr. Gottlieb’s editorial expertise left an indelible mark on the works of notable authors including John le Carré, Toni Morrison, John Cheever, Joseph Heller, Doris Lessing, and Chaim Potok. He also edited science fiction by Michael Crichton and Ray Bradbury, histories by Antonia Fraser and Barbara Tuchman, memoirs by former President Bill Clinton and Katharine Graham, and works by Jessica Mitford and Anthony Burgess.

Over three decades at Simon & Schuster and Knopf, Robert Gottlieb transformed numerous manuscripts into highly acclaimed books that not only sold millions of copies but also garnered awards, bringing both wealth and fame to the authors. Colleagues recognized his incisiveness and sensitivity toward writers’ fragile egos, which earned him a devoted following of authors. He eventually became the President and Editor-in-Chief of Knopf.

In a surprising career move in 1987, Mr. Gottlieb transitioned from the relative anonymity and tranquility of book publishing to take on one of American journalism’s most prominent roles as the third editor in the 62-year history of The New Yorker. He succeeded the legendary William Shawn, who had held the position for 35 years following the magazine’s founding editor, Harold Ross.

Mr. Gottlieb’s appointment by S.I. Newhouse Jr., whose family owned both Random House (Knopf’s parent company) and The New Yorker, caused a stir among the staff. A petition signed by 154 writers, editors, and others protested the forced retirement of Mr. Shawn, who had made journalism history with groundbreaking articles that went on to become bestselling books, such as John Hersey’s “Hiroshima,” Hannah Arendt’s “Eichmann in Jerusalem,” and Rachel Carson’s “Silent Spring.”

While acknowledging Mr. Gottlieb’s reputation for brilliance, the petition urged him to step aside in favor of Charles McGrath, an insider and the magazine’s fiction editor, to better uphold its traditions. However, Mr. Gottlieb stood his ground, immersing himself in the fast-paced world of weekly deadlines and navigating the complex relationships between editors and writers, which differed greatly from his extensive experience in book publishing.

“In a publishing house, you are in a strictly service job as an editor,” Mr. Gottlieb explained in his 2012 anthology, “The Art of Making Magazines.” “Your job is to serve the book and the writer.” However, at The New Yorker, he noted, “You are the living god. You are not there to please the writers, but the writers are there to satisfy you because they want to be in the magazine.”

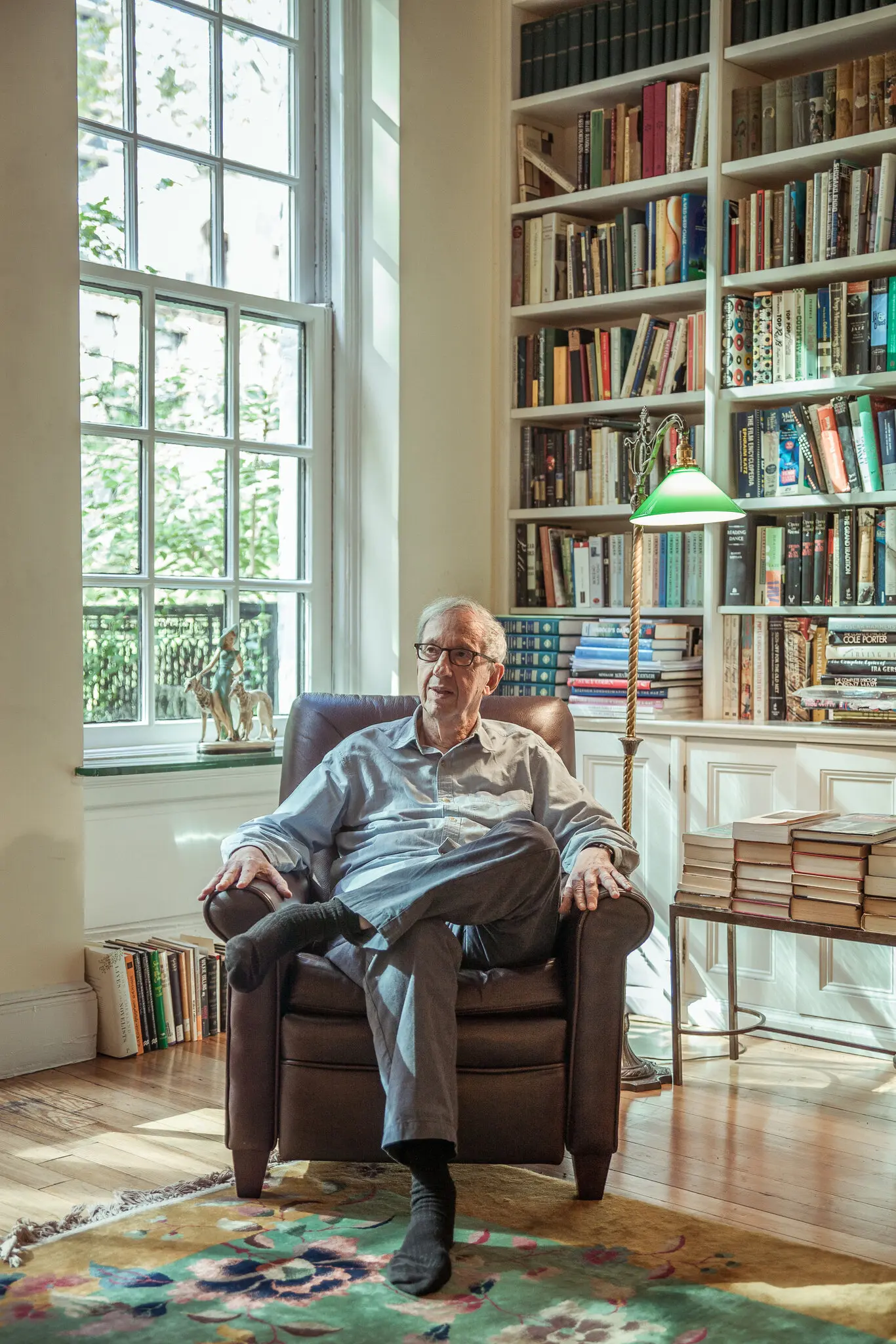

Contrasting with his distinguished and formal predecessor, Mr. Gottlieb had a quirky personality, collecting kitsch items such as plastic women’s handbags. He was a devoted enthusiast of classical ballet and a peculiar Anglophile who affectionately referred to writers as “dear boy.” He preferred hot dogs in Central Park or sandwiches at his desk over attending gossipy magazine lunches. With his distinct appearance, including a long face, thick glasses, and thinning hair, he roamed the office in worn-out sneakers, baggy pants, and rumpled polo shirts, engaging with the staff.

Alleviating the concerns of many devoted New Yorker readers, Mr. Gottlieb introduced few and mostly minor changes during his five-year tenure. He welcomed new contributors, including journalist Raymond Bonner, essayist Judith Thurman, and poet Diane Ackerman, and published fiction by Robert Stone and Richard Ford. The magazine also hired new critics and opened up Talk of the Town commentaries to a broader range of writers, eliminating the anonymity that had characterized them. Gradually, Mr. Gottlieb earned the trust and affection of most of the staff.

In 1992, Tina Brown, the British editor of Vanity Fair, replaced Mr. Gottlieb in a cordial transition and introduced splashy changes to the magazine. Some hailed the updates as lively and topical, while traditionalists decried them as vulgar, particularly a controversial cover featuring Eustace Tilley, the magazine’s iconic dandy, portrayed as an acne-prone teenager with a gold earring, squinting at a handbill for a Times Square sex shop.

Following his tenure at The New Yorker, Mr. Gottlieb returned to editing for Knopf, worked as a dance critic for The New York Observer, compiled anthologies on dance, jazz, and lyrics, and authored several books. His memoir, “Avid Reader: A Life,” published in 2016, offered insights into the pros and cons of the literary world.

Among his sharp observations, Mr. Gottlieb shared his candid opinions about authors, including V.S. Naipaul, whom he referred to as “a snob,” and Katharine Graham, whose “sense of entitlement was sometimes hard to deal with.” His memoir also included comments on William Gaddis, whom he described as “unrelentingly disgruntled,” and Roald Dahl, whom he labeled “erratic and churlish.”

Robert Adams Gottlieb was born on April 29, 1931, in Manhattan to Charles and Martha Gottlieb. His father was a lawyer, and his mother was a teacher. Growing up on the Upper West Side, Robert found solace in books and became an avid reader. Even as a teenager, he devoured literature, reading Leo Tolstoy’s “War and Peace” in a day and Marcel Proust’s monumental work “Remembrance of Things Past” in a week.

At Columbia University, Mr. Gottlieb pursued his passion for literature and graduated with a bachelor’s degree, receiving the prestigious Phi Beta Kappa key in 1952. He later earned a postgraduate degree from the University of Cambridge in England in 1954.

Mr. Gottlieb married Muriel Higgins in 1952, and they had a son named Roger before divorcing. In 1969, he married actress Maria Tucci, with whom he had two children, Lizzie and Nicky. In addition to his wife, he is survived by his children and twin grandsons.

In 1955, Mr. Gottlieb joined Simon & Schuster as an assistant to editor Jack Goodman. After Mr. Goodman’s passing in 1957, he assumed the role of senior editor, overseeing books by prominent figures such as drama critic Walter Kerr and humorist S.J. Perelman, as well as novels and nonfiction works. In 1965, he was appointed Editor-in-Chief.

One of his career highlights at Simon & Schuster was discovering a manuscript titled “Catch-18” by advertising copywriter Joseph Heller. Due to the similarity to Leon Uris’s novel “Mila 18,” the title was changed, and in 1961, Joseph Heller’s book was published as “Catch-22.”

The darkly comedic anti-war novel “Catch-22” became a long-lasting bestseller and left a significant impact on American culture. The term “catch-22” entered the lexicon to describe a paradoxical situation where one is trapped by contradictory rules or circumstances. The novel’s portrayal of World War II airmen and the infamous “catch” they faced resonated with readers and further solidified Mr. Gottlieb’s reputation as an esteemed editor.

In 1968, Robert Gottlieb joined Alfred A. Knopf as Vice President and Editor-in-Chief. One of his notable editing achievements was working on Robert Caro’s Pulitzer Prize-winning biography of Robert Moses, titled “The Power Broker” (1974). Mr. Gottlieb, while collaborating with the author, made significant cuts, removing 400,000 words from the original one-million-word manuscript. Despite the challenging process, their collaboration endured for five decades and became the subject of a 2022 documentary, “Turn Every Page,” directed by Lizzie Gottlieb, Robert’s daughter.

Reflecting his versatility, Mr. Gottlieb also edited “Miss Piggy’s Guide to Life” (1981) under the pseudonym of Henry Beard, ghostwriting for the beloved Muppets character. He also edited Salman Rushdie’s controversial novel “The Satanic Verses” (1988), which led to Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini issuing a fatwa calling for the author’s death.

Mr. Gottlieb assumed the role of President of Knopf in 1973, further solidifying his influence in the publishing industry. His love for literature and penchant for kitsch were evident in his homes in Manhattan, East Hampton, Miami, and Paris. His New York townhouse featured towering bookcases, a portrait of George Eliot, and a photo of the Chekhov family, creating a literary sanctuary intermingled with his affinity for plastic women’s handbags and quirky 3-D dog posters he acquired from flea markets.

In addition to his memoir, Mr. Gottlieb authored biographies of actress Sarah Bernhardt and choreographer George Balanchine, a book about the children of Charles Dickens, and wrote articles for The New York Review of Books and other publications.

His later books included “Near-Death Experiences … and Others” (2018), a collection of essays primarily written for The New York Review of Books, and “Garbo” (2021), a biography delving into the enigmatic life of the iconic film star. However, Mr. Gottlieb always saw himself as an editor, a figure floating somewhat in the background.

“The editor’s relationship to a book should be an invisible one,” Mr. Gottlieb expressed in an interview with The Paris Review in 1994. “The last thing anyone reading ‘Jane Eyre’ would want to know, for example, is that I had convinced Charlotte Brontë that the first Mrs. Rochester should go up in flames.”

The passing of Robert Gottlieb marks the end of an era in the world of publishing. His deft touch and astute editorial skills shaped the careers of numerous acclaimed writers, leaving an indelible mark on the literary landscape of the 20th century. The legacy of this illustrious editor will continue to inspire and influence generations of readers and writers alike.